Research Article

Vitamin Contents of Extracts of Dialium Guineense Stem Bark

Abu OD*, Onoagbe IO and Obahiagbon O

1Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria

2Physiology Division, Nigerian Institute for Oil Palm Research (NIFOR), Benin City, Nigeria

Received Date: 20/10/2020; Published Date: 20/11/2020

*Corresponding author: Osahon Abu, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria

DOI: 10.46718/JBGSR.2020.05.000126

Cite this article: Abu OD*, Onoagbe IO and Obahiagbon O. Vitamin Contents of Extracts of Dialium Guineense Stem Bark. Op Acc J Bio Sci & Res 4(1)-2020.

Abstract

Background: The use of medicinal plants in alternative medicine has received huge attention in recent times. Dialium guineense belongs to the Leguminosae family, and grows in dense forests in Africa along the southern edge of the Sahel. The bark, leaves and fruits of the plant have medicinal properties and are used to treat diseases such as stomatitis, toothache, fever, diarrhea, palpitations, and microbial infections. The present study evaluated the vitamin contents of aqueous and ethanol extracts of Dialium guineense stem bark.

Materials and Methods: The stem bark of the plant was extracted using distilled water and absolute ethanol according to standard method, and subjected to high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The present study evaluated the vitamin contents of aqueous and ethanol extracts of Dialium guineense stem bark.

Results: The results of vitamin analysis revealed the presence of high concentrations of the B-group of vitamins in both extracts. The concentrations of the B-group of vitamins, and vitamins C and E were significantly higher in the ethanol extract than in the aqueous extract (p < 0.05), but there was no significant difference in the concentration of vitamin A between the two extracts (p > 0.05).

Conclusion: These results suggest that aqueous and ethanol stem bark extracts of D. guineense stem bark are rich sources (reservoirs) of important vitamins.

Keywords: High performance liquid chromatography, Dialium guineense, Extract, Stem bark, Vitamin

Introduction

Medicinal plants are re-emerging health aids which have gained huge attention in recent times [1]. Dialium guineense (Velvet Tamarind), is a tall, tropical, fruit-bearing tree. It belongs to the Leguminosae family, and grows in dense forests in Africa along the southern edge of the Sahel. The bark, leaves and fruits of the plant have medicinal properties and are used to treat diseases such as stomatitis, toothache, fever, diarrhea, palpitations, and microbial infections [1]. Each fruit typically has one hard, flat, round, brown seed, typically 7 -8mm across and 3 mm thick [2]. The seed somewhat resembles a watermelon seed (Citrullus lanatus). Some have two seeds. The seeds are shiny, and coated with a thin layer of starch. The pulp is edible and may be eaten raw or soaked in water and consumed as a beverage [2]. The bitter leaves are ingredients in a Ghanaian dish called domoda. Its wood is hard and heavy, and used for construction. The wood is also used for firewood and charcoal production [2].

Water-soluble vitamins include the vitamin B-complex and vitamin C, and are essential nutrients needed daily by the body in very small quantities. The B-complex vitamins can be found in a variety of enriched foods like cereal grains and breads, as well as other foods such as meat, poultry, eggs, fish, milk, legumes, and fresh vegetables. Vitamin C can be found in many fruits and vegetables [3]. Deficiencies of B vitamins and vitamin C can be found in alcoholics, elderly and in those on limited diets [4]. Folic acid (folate) deficiency is common in pregnancy. Similarly, Vegans are prone to vitamin B12 deficiency, because it is not present in plant foods. Some conditions such as exposure to cigarette smoke, environmental stress, growth, and sickness warrant an increase in vitamin C intake. Over-consumption of the water-soluble vitamins is generally not a problem, especially if the nutrients are obtained through food. Large amounts of vitamin B-complex and vitamin C supplements and multivitamins are not recommended [3-5]. The B-group of vitamins are essential for the function of several enzymes, biosynthesis of neurotransmitters and normal carbohydrate, lipid, and protein metabolism [6,7].

Animal studies suggest that nicotinamide protects pancreatic β-cells from autoimmune destruction by maintaining intracellular levels of NAD+ while inhibiting the activity of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), an enzyme involved in DNA repair [8]. Pharmaceutical doses of thiamine (B1) and niacin (B3) may be useful in preventing renal and cardiovascular complications in individuals with T2DM. Thiamine deficiency may augment hyperglycemia-induced tissue damage. Its supplementation promotes endothelial function and slows the progression of vascular disease and oxidative stress [9]. A small randomized controlled trial revealed that administration of 150 mg/kg bwt of thiamine daily for 1 month, significantly reduced glucose and leptin concentrations in individuals with T2DM [10]. It has been suggested that thiamine supplementation may prevent and reverse early stage nephropathy [11]. According to the British National Formulary [12], nicotinic acid can be used in doses 1.5-3g/kg bwt daily to lower cholesterol and triacylglycerols by inhibiting their synthesis, while raising HDL-C. It is often used in combination with a statin. A balanced and varied diet containing fruit and vegetables can contribute towards reducing the progression of diabetic complications by providing an adequate intake of antioxidant vitamins [13]. Vitamin C is structurally similar to glucose and may therefore, compete with glucose for transportation into cells. In the presence of hyperglycemia, the uptake of vitamin C into cells appears impaired. It functions as an antioxidant and inhibits the intracellular accumulation of sorbitol. Vitamin C reduces the glycosylation of proteins. Vitamin D enhances insulin secretion and promotes β-cell survival by modulating the generation and effects of cytokines. The anti-apoptotic action of vitamin D is mediated via the down-regulation of fas-related pathways (fas/fas-L) [14]. Vitamin D enhances insulin sensitivity by stimulating the expression of insulin receptors and/ or by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-δ (PPAR- δ) [15]. The PPAR-δ is implicated in the regulation of fatty acid metabolism in skeletal muscles and adipose tissue. The indirect effect of vitamin D is exerted by regulating calcium flux through the cell membrane and intracellular calcium by ryanodine receptor (RR). Oxidative stress and free radicals-induced damage to blood vessels and organs are significantly reduced by antioxidant potential of vitamins A, C, and E, and low levels of vitamin E are associated with increased incidence of type-2 diabetes mellitus T2DM [16].

Materials and Methods

The plant leaves were obtained from a forest area in Benin and identified at the Department of Plant Biology and Biotechnology with voucher number UBHD330, after which the bark was obtained. Preparation and extraction was carried out using the method of Abu et al., [17]. The aqueous and ethanol extracts were concentrated using rotary evaporator and made into powder by lyophilisation.

Vitamins Analysises

Vitamins analyses were carried out on the aqueous and ethanol extracts using High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) [18].

Instrumentation/Equipment

The HPLC was performed using Shimadzu system which consisted of a column oven (model CTO-10ASVP), UV-visible diode-array detector (model SPD-M10 AVP), degasser (model DGU 14A), and liquid chromatography pump (model LC-10AT-VP). Shimadzu software was used to calculate peak areas. The digested extract (20µL) was injected into the HPLC machine with a syringe. The HPLC column used was reversed-phase Discovery C18 (150 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 µm; #504955). Reagents such as methanol and K2HPO4 used were of analytical grade. Water used was double distilled and deionized. Stock and standard solutions of water-soluble vitamins were prepared in mobile phase. Five different concentrations of each standard were used to prepare the calibration curve. These solutions were sonicated and stored in dark glass flasks, to protect them from light, and kept refrigerated. A calibration curve was prepared for each vitamin. Correlation coefficients on the basis of plots of concentration (µg/mL) for each vitamin against peak area (mAU) were greater than 0.999.

Sample Preparation (Solid-Phase Extraction, SPE)

Sample treatment consisted of SPE with Sep-Pak C18 (500 mg) cartridges that enabled separation of water-soluble vitamins and removed most of the interfering components. Four parts of deionised water (20 g) were added to one part of each extract (5 g) (dilution factor (DF) = 5). The mixture was homogenized using a homogenizer at medium speed for 1 min. The homogenized samples were centrifuged at 14, 000 g for 10 min. The SPE method of Choi and Mason (2000) was used for extraction of water-soluble vitamins. The stationary phase was flushed with 10mL methanol and 10 mL water (pH 4.2) to activate the stationary phase. The resultant supernatant (10mL) was then loaded into the column. Acidified water was prepared by adding 0.005M HCl solution drop by drop with stirring to distilled water until the pH reached a predetermined value. The sample was first eluted with 5 mL acidified water (pH 4.2), followed by 10 mL methanol at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The eluent was collected in a beaker and evaporated to dryness. The resultant residue was dissolved in mobile phase. Before the commencement of HPLC, all samples were filtered through 0.45 µm pore size FP 30/45 CAS filters at 7 bar max. Samples of water-soluble vitamins (20µL) were then injected into the HPLC column. The column eluate was monitored with a photodiode-array detector at 265 nm for vitamin C, 234nm for thiamine, 266 nm for vitamin B2, 324nm for vitamin B6, 282 nm for folic acid, 204 nm for biotin and cobalamin, 261 nm for vitamin B3, 324nm for rectinol, 295 nm for α-tocopherol, and 245 nm for ascorbic acid. The mobile phase was filtered through a 0.45µm membrane and degassed by sonication before use. The mobile phase was 0.1 mol/L KH2PO4 (pH 7)-methanol (90:10, v/v). The flow rate was 0.7 mL/min. The column was operated at room temperature (25 °C). Chromatographic peak data were integrated up to 39 min. Identification of compounds was achieved by comparing their retention times and UV spectra with those of standards. Concentrations of the water-soluble vitamins were automatically calculated from integrated areas of the sample, and the corresponding standards using the software installed in the equipment.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (16.0).

Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Outcome of Vitamin Analysis

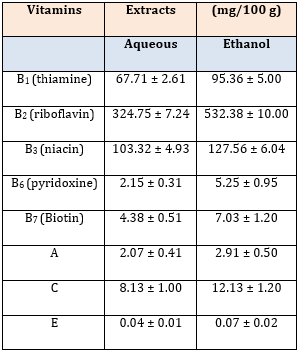

Vitamin analysis revealed the presence of high concentrations of the B-group of vitamins in both extracts. The concentrations of the B-group of vitamins, and vitamins C and E were significantly higher in the ethanol extract than in the aqueous extract (p < 0.05), but there was no significant difference in the concentration of vitamin A between the two extracts (p > 0.05; Table 1).

Table 1: Vitamin Composition of Pulverized Stem Bark of Dialium guineense.

Data are vitamin composition of aqueous and ethanol stem bark extracts of D. guineense, and are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Discussion

The B-group of vitamins are essential for the function of several enzymes, biosynthesis of neurotransmitters and normal carbohydrate, lipid, and protein metabolism [6,7]. Thiamin or vitamin B1, helps to release energy from foods, promotes normal appetite, and plays a role in muscle contraction and conduction of nerve signals [5]. Alcoholics are especially prone to thiamin deficiency because alcohol reduces thiamin absorption and storage, and excess alcohol consumption often replaces food or meals. Symptoms of thiamin deficiency include mental confusion, muscle weakness, wasting, water retention (edema), enlarged heart, and beriberi [5].

Riboflavin or vitamin B2, helps to release energy from foods, and is also important for growth, development and function of cells. It plays a role in the conversion of the amino acid tryptophan to niacin [19]. Groups at risk of riboflavin inadequacy include vegan athletes and pregnant and breastfeeding women and their babies. Symptoms of deficiency include skin disorders, cracks at the corners of the mouth, hair loss, itchy and red eyes, reproductive problems, and cataracts [19].

Niacin or vitamin B3, is involved in energy production and critical cellular functions. Pellagra occurs as a result of severe niacin deficiency, and symptoms include skin problems, digestive problem, and mental confusion [19]. Consumption of large doses of niacin supplements beyond 35mg/day may cause flushed skin, rashes, hypotension symptoms, or liver damage. However, it is not a problem if it is obtained through food [19].

Vitamin B6, otherwise known as pyridoxine, pyridoxal or pyridoxamine, aids in protein metabolism, red blood cell formation, and behaves as an antioxidant molecule. It is also involved in the synthesis of neurotransmitters and hemoglobin [20]. Vitamin B6 deficiency is uncommon and usually associated with low concentrations of other B-complex vitamins, like vitamin B12 and folic acid. Deficiency symptoms include dermatitis, swollen tongue, peripheral neuropathy, anemia, depression and confusion, and weakened immune function. A vitamin B6 deficiency in infants can cause irritability, acute hearing problem, and convulsive seizures [20]. Although over-consumption of vitamin B6 from food sources have not been reported to cause adverse health effects, chronic excess doses of it results in nerve damage [20].

Biotin helps release energy from carbohydrates and aids in the metabolism of fats, proteins and carbohydrates from food. The Adequate Intake (AI) for Biotin is 30 mcg/day for adult males and females [21]. Biotin deficiency is uncommon. A few of the symptoms of biotin deficiency include hair loss, skin rashes, and brittle nails, and for this reason biotin supplements are often promoted for hair, skin, and nail health. However, these claims are only a few case reports and small studies [21].

Vitamin C participates in collagen synthesis, wound healing, bone and tooth formation, strengthens blood vessel walls, improves immune system function, promotes absorption and utilization of iron, and acts as an antioxidant. It works with vitamin E as an antioxidant, and plays a crucial role in neutralizing free radicals [3]. Vitamin C may prevent or delay the development of certain cancers, heart disease, and other diseases in which oxidative stress plays a causal role [3]. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for vitamin C is 90 mg/day for adult males and 75 mg/day for adult females. For cigarette smokers, the RDA for vitamin C increases by 35 mg/day, in order to counteract the oxidative effects of nicotine. Vitamin C recommendations also increase during pregnancy and lactation. Severe vitamin C deficiency may result in scurvy, causing fatigue and loss of collagen strength [3]. Loss of collagen results in loose teeth, bleeding and swollen gums, and improper wound healing. Factors such as environmental stress such as air and noise pollution, wound healing, growth (children from 0-12 months, and pregnant women), fever and infection, and smoker increase vitamin C requirements [3].

There are eight naturally occurring forms of vitamin E; namely, the alpha, beta, gamma and delta classes of tocopherol and tocotrienol, which are synthesised by plants from homogentisic acid. Alpha-and gamma-tocopherols are the two major forms of the vitamin, with the relative proportions of these depending on the source. The richest dietary sources of vitamin E are edible vegetable oils as they contain all the different homologues in varying proportions. Among the tocopherols, the alpha- and gamma-tocopherols are found in serum and red blood cells, with alpha-tocopherol present in the highest concentration [22,23].

Beta- and delta-tocopherols are present in plasma in minute concentrations. The preferential distribution of alpha-tocopherol in humans over the other forms of tocopherol stems from the faster metabolism of the other forms and from the alpha-tocopherol transfer protein (alpha-TTP). This is due to the binding affinity of alpha-tocopherol with alpha-TTP. Most of the absorbed beta-, gamma-and delta-tocopherols are secreted into the bile and excreted in the faeces, while alpha-tocopherol is largely excreted in the urine. The alpha-tocopherol form also accumulates in the non-hepatic tissues, particularly at sites where free radical production is greatest, such as in the membranes of mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum of the heart and lungs [24,25].

Vitamin A is a group of fat-soluble compounds that can be differentiated into two categories, depending on whether the food source is an animal or a plant: vitamin A from animal source is called preformed vitamin A or retinol, while vitamin A present in fruits and vegetables is called provitamin A carotenoid, and can be cleaved to retinol [26,27]. The carotenoid beta-carotene is most efficiently converted to retinol, making it an important vitamin A source. Vitamin A promotes vision (especially night vision), growth and development, gene regulation, cell and tissue formation, and programming and communication needed for reproduction and the proper development of an embryo. It also promotes immune function, maintenance of normal skin and mucous membranes, and normal iron metabolism [28,29].

In this study, the concentrations of the B-group of vitamins, and vitamins C and E were significantly higher in the ethanol extract than in the aqueous extract, but there was no significant difference in the concentration of vitamin A between the two extracts.

Conclusion

The results obtained in this study suggest that aqueous and ethanol stem bark extracts of D. guineense stem bark are rich sources (reservoirs) of important vitamins.

References

2. Dalziel JM, Hutchison J (1973) Flora of West Tropical Africa. (2nd edn). The White friars Press Ltd. London, UK, 1: 561.

3. Carr AC ,Maggini S (2017) Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients 9(11): 1211.

4. National Institute of Health (2018) Dietary Supplement Fact Sheets.

5. Berdanier CD, Berdanier L (2015) Advanced Nutrition: Macronutrients, Micronutrients, and Metabolism, Second Edition. Oakville: CRC Press.

7. Sarubin A (2000) The Health Professional’s Guide to Popular Dietary Supplement. The American Dietetic Association, Chicago, USA.

8. Shils ME, Olson JA, Moshe S (1999) Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. Williams & Wilkins; Lippincott, Philadelphia, USA.

12. British National Formulary (BNF) (2013) Medicine and Health Science Books (66th edn), Pharmaceutical Press, London and Chicago.

13. Martin C (2013) The role of vitamins in the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes and its Complications. J. Diabetes Nursing 17: 376-383.

17. Abu OD, Imafidon KE, Iribhogbe ME (2015) Biochemical effect of aqueous leaf extract of Icacina trichanta Oliv. On urea, creatinine and kidney oxidative status in CCl4-induced Wistar rats. Nigerian Journal of Life Sciences 5(1): 85-89.

18. AOAC (2002) Official methods of analysis,Association of official analytical chemists (18th edn), Washington, DC, USA.

19. Duyff RL (2017) Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Complete Food and Nutrition Guide, Fifth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston.

20. Stipanuk MH, Caudill MA (2018) Biochemical, Physiological, Molecular Aspects of Human Nutrition, Fourth Edition. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

21. Gropper SA, Smith JL, Carr TP (2018) Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism, Seventh Edition. MA: Cengage Learning, Boston.

22. Niki E, Traber MG (2012) A history of vitamin E. Ann Nutr Metab 61: 207-212.

23. Zingg JM (2007) Vitamin E: An overview of major research directions. Mol Aspects Med 28: 400-422.

27. Bellagio Brief (1993) Vitamin A deficiency and childhood mortality. Bulletin of the Pan American Health Organization 27: 192-197.

29. Sommer A (1992) Vitamin A deficiency and childhood mortality. Lancet 339: 864.

Recent Comments