Case Report

Merkel Cell Carcinoma as a Biomarker of Immune System Disfunction : A Case Report

Giovanni Cestaro*, Fabio Cavallo, Monica Zese, Daniela Prando, Ferdinando Agresta

1UOC CHIRURGIA, Ospedale Civile di Adria, ULSS 5 POLESANA, Piazzale degli Etruschi -Adria (RO),Italy

2UOC CHIRURGIA GENERALE E D’URGENZA, Ospedale di Circolo e Fondazione Macchi,ASST SETTE LAGHI Viale L. Borri – Varese,Italy

Received Date: 15/09/2020; Published Date: 29/09/2020

*Corresponding author: Giovanni Cestaro, UOC CHIRURGIA,Ospedale Civile di Adria,ULSS 5 POLESANA, Piazzale degli Etruschi -Adria (RO), Italy

DOI: 10.46718/JBGSR.2020.04.000106

Cite this article: Giovanni Cestaro, Fabio Cavallo, Merkel Cell Carcinoma as a Biomarker of Immune System Disfunction: A Case Report. Op Acc J Bio Sci & Res 4(1)-2020.

Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) represents a rare tumor of the skin. It is a neuroendocrine tumor, firstly described as “a trabecular carcinoma of the skin” by Toker in 1972 [1]. It occurs in elderly and immune - compromised patients typically. Most frequent tumor sites are head and neck (40-60%), trunk (33%) and more rarely the extremities (10-20%). Instead the ileum represents the most frequent localization of all neuroendocrine tumors [2]. The best therapy for this type of tumor is still strongly debated. Nowadays we can consider as therapeutic options surgical excision, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and biological agents, according a correct classification of disease progression (stages): localized or metastatic MCC. Most cases are detected accidentally. Indeed, an MCC often appears like a cutaneous mass of the skin, with no specific features, presenting as red/pink, blue/violaceous, skin colored painless lesions in patient with a “long-lasting” clinical history, usually not related to neuroendocrine tumors [3]. Hereby we described an interesting case in a male patient with an important “oncological background”.

Case Report

A 74-male patient, affected by hypertension, presented in November 2019 at our Surgical Department with a smallsized mass arising from the posterior aspect of distal right leg, above Achille's tendon area. His previous clinical history was characterized by four different tumors: in 1999 he was submitted to left kidney resection, in 2006 he underwent to a duodenocephalopancreatectomy according to Whipple technique (for pancreatic neoplasm), in 2018 he was treated by radical prostatectomy with extensive lymphadenectomy for prostate cancer and at the beginning of 2019 he was affected by myelofibrosis treated by biological therapy.

We treated the leg mass performing a wide surgical excision of the lesion. The unexpected histopathological result was MCC infiltrating deeply the ventral aspect of the lesion.

Consequently, the patient was submitted to the following exams:

a. total body CT – PET (with 18 Fluoro Deoxy Glucose - 18F-FDG) scan, with no detected metastasis;

b. lymphography with radio-metabolic marker, revealing that affected leg lymphatic drainage was localized in right inguinal region.

We finally decided to re-do excision of leg scar and to remove lymphatic inguinal nodes localized at the right inguinal area.

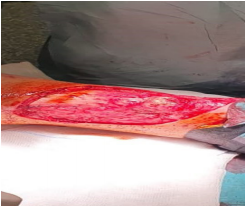

After second surgical biopsy, the histological result confirmed a persistent neoplasia, with an infiltrated margin of the specimen too. For this reason, we performed a third surgical operation: widening of scar, removal of three metastasis in transit localized in right the popliteal area, clinically palpable but targeted by UltraSound Scan support, and a completion of right inguinal lymphadenectomy (Figures 1-3). At histopathological examination, no other metastasis was detected in inguinal lymph nodes and metastasis in transit were completely excised.

Consequently, satisfying wound healing of the Achille’s tendon region was promoted by hydro-fiber dressings and Negative Wound Pressure Therapy (portable NPWT) for 2 weeks and the patient was sent to Oncological Department for radiotherapy and future follow-up.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Discussion

Merkel Cell Carcinoma is a challenging and rare cutaneous neoplasm, with an incidence of about 5 cases for 1 million population [4]. This carcinoma typically has immunophenotypic similarities to Merkel cells of the skin: they are localized in the basal layer of the skin, close to nervous terminals forming mechanoreceptors and they are epithelial derived cells. Nevertheless, MCC origin is unclear: lymphoid B-cell markers are noticed in several cases, while other authors proposed an origin by dermal mesenchymal stem cells. Merkel Cell Carcinoma generally occurs in elderly people, more frequently in male patients, with immunological system dysfunction due to cancer(s), HIV, HCV, other severe infections or immunosuppression posttransplantation [5]. Clinically this neoplasm has a cystic or nodular aspect, sometimes presenting as a bleeding lesion or a plaque. Tumor size ranges from 2 to 200 mm, but it is usually < 20 mm.

Histochemical aspects of this kind of tumor are CK-20 (low molecular weight cytokeratin), NSE (neuro specific enolase) and NFP (neurofilament protein) expression [6]. In 2008 Feng and coll. found a novel viral sequence in four Merkel cell carcinoma cases. These data led to a new targeted therapy of neoplasm. Indeed, the related Merkel cell carcinoma virus is a polyomavirus, defined MCPyV (Merkel Cell Carcinoma PolyomaVirus), and it especially encodes large T-antigens that bind to host protein, promoting viral and cellular replication by oncosuppressor gene p53 blockade. This polyomavirus is highly expressed (80% of MCC) in local and metastatic disease, consequently it represents an interesting target for novel biological therapy which can be useful in most severe cases [7].

At early stage, surgical excision is the primary treatment with sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). Excision should be done with at least 1 cm margin in case of local disease. Tissue reconstruction depends on tumor size, tumor site and histological result; we can consider several options such as direct suture, local flap, microsurgery flap, dermal regeneration template followed by skin graft, NPWT. If a positive SLNB is obtained, a complete lymph node dissection (CLND) is required. MCC is also radiosensitive, consequently radiotherapy (RT) is a valid therapeutic tool, especially to treat locally advanced neoplasm and to reduce local recurrence. As concern as medical treatment, in case of metastatic disease, etoposide and carboplatin represent the most common chemotherapeutic agents. MCC is very sensitive to chemotherapy, but duration of response is un clear and tumors often recur within 4-15 months. Immunotherapy is the most recent and innovative treatment and its use can be also related to MCVyP [8]. These tumors exhibit viral peptides that can be destroyed by cellular immune responses. Several therapies are based on monoclonal antibodies targeting programmed cell death receptor 1 / programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD – 1 / PD – L1) interaction reveal promising results for metastatic MCC. The binding of PD - L1 to PD – 1 on cytotoxic T cells inhibits their tumor-killing activity. PD – L1 is frequently expressed on MCC tumor cells and peritumoral immune cells. Pembrolizumab is an anti PD-1 antibody approved for the treatment of melanoma and non - small cell lung cancer [9] and it was recently approved also for metastatic MCC treatment. Another therapeutic option can be a peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PPRT): MCC expresses somatostatin receptors and then radiolabeled somatostatin analogue is taken up by tumor to be effective.

Our report can represent an interesting example of a rare neoplasm as a biomarker of immune system dysfunction. It is worthwhile to highlight that our patient has a clinical history characterized by four past tumors, all successfully treated.

References

1. Toker C (1972) Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Archivers for dermatological research 105: 107-110.

2. Pink R, Ehrmann J, Molitor M, Trvdy P, Michl P, et al. (2012) Merkel cell car-cinoma. A review. Biomed Pap Med FAC Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 156(3): 213 -217.

3. Amaral T, Leiter U, Garbe C (2017) Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagno-sis and therapy. Rev End Met Dis 18: 517-532.

4. Schadendorf D, Lebbè C, zur Hausen A, Avril M-F, Hariharan S, et al. (2017) Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, prognosis, therapy and unmet medical needs.; Eur J Canc 71: 53-69.

5. De Paola M, Poggiali S, Miracco C, Pisani C, Batsikota A, et al. (2014) Merkel cell carcinoma of the lower limb. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 149 (3): 378-381

6. Cassler NM, Merrill D, Bichakjian CK, Brownell I (2016) Merkel Cell Carcinoma Therapeutic Update. Curr Treat Options Oncol 17(7): 36.

7. Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS (2008) Clonal Integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science 319 (5866): 1096-1100.

8. Cestaro G, Quarto G, De Monti M, Fasolini F, De Fazio M, et al. (2018) New and emerging treatments for metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Panminerva Med 60 (1): 39-40.

9. Asgari MM, Sokil MM, Warton EM, Iyer J, Paulson K.G, et al. (2014) Effect of host, tumor, diagnostic, and treatment variables on outcomes in a large cohort with Merkel cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol 150(7): 716-723.

Recent Comments