Research Article

Epigastric Pain Secondary to Accumulation of Extravasated Fluid in Pararenal and Perirenal Areas, in Shock Due to Dengue

Melisa Milena Galván Suárez, Mauricio Miguel Meza Delgado, Jorge Enrique Martínez López, José Antonio Reyes Pinto, Juan Carlos Rivera Acosta, Angie Katerine Rodríguez Paredes, Lina Marcela Álvarez Vides, Adams Mattos Amarís, Ever Raul Garcia Otero

General Physician, Universidad del Sinú, Colombia

Intern Physician, Corporación Universitaria Rafael Núñez, Cartagena, Colombia.

General Physician, Universidad del Sinú, Montería, Colombia

General Physician, Universidad del Sinú de Montería, Colombia

General Physician, Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia

General Physician, Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia

General Physician, Universidad del Sinú, Montería, Colombia

General Physician, Corporación Universitaria Rafael Núñez

General Physician, Corporación Universitaria Rafael Núñez

Received Date: 13/10/2021; Published Date: 19/10/2021

*Corresponding author: Melisa Milena Galván Suárez, General Physician, Universisad del Sinú, Colombia

DOI: 10.46718/JBGSR.2021.10.000234

Cite this article: Melisa Milena Galván Suárez, Mauricio Miguel Meza Delgado, Jorge Enrique Martínez López, José Antonio Reyes Pinto, Juan Carlos Rivera Acosta, Angie Katerine Rodríguez Paredes, Lina Marcela Álvarez Vides, Adams Mattos Amarís, Ever Raul Garcia Otero. Epigastric Pain Secondary to Accumulation of Extravasated Fluid in Pararenal and Perirenal Areas, in Shock Due to Dengue.

SUMMARY

Dengue is the viral disease transmitted by arthropods that causes the most morbidity and mortality worldwide. In today's world, this arbovirus is considered the tenth cause of death, especially in pediatric ages. The infection can be asymptomatic or express with a wide clinical spectrum that includes severe and non-severe expressions. The most severe manifestations, previously called dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome, occur in less than 5% of cases. With the recognition of the severe forms of dengue, the disease has received great global attention and is today considered the most important viral hemorrhagic disease. Thanks to the fact that some national and international studies have reported that the unusual manifestations of dengue hemorrhagic fever are relatively frequent and are associated with a higher mortality rate on the recognition of severe forms of dengue, the disease has received great worldwide attention and is now considered the most important viral hemorrhagic disease.

KEYWORDS: Dengue; Epigastric pain; Extravasated fluid; Dengue shock.

Introduction

Dengue is an infectious disease, dynamic and systemic type, caused by the bite of the Aedes aegypti mosquito (female, which is hematophagous) mainly, transmitting the virus of the flaviviridae family, infectiously between 8 to 12 days, until its death, approximately 45 days later [1].

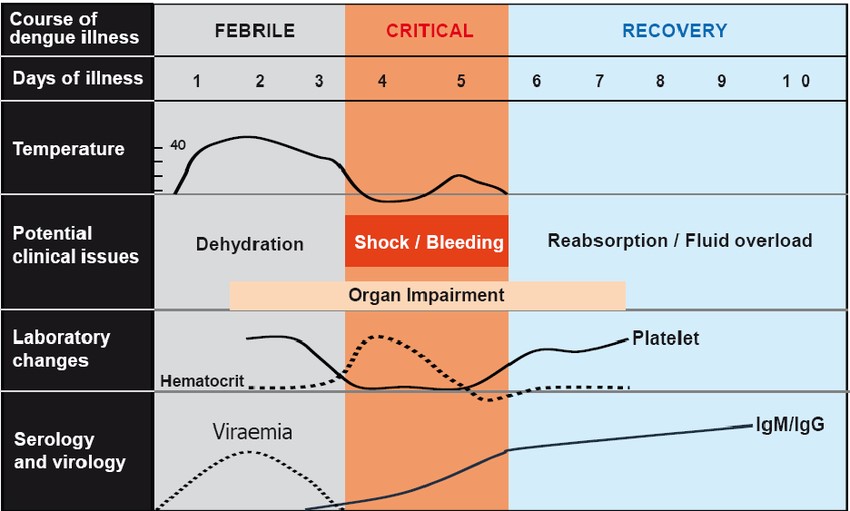

It develops in three phases (feverish, critical and recovery) (figure 1), well described, with specific symptoms as well as the duration ranges, showing an observable evolution. Its symptoms generally include variants in infected patients, such as fever and headache, arthralgia and myalgia, and occasionally cough. Its diagnosis is by serological detection of IgM and ELISA test; as well as a simple treatment, low cost but efficient [2].

Figure 1:

Dengue has 4 fully identified serotypes (DENV - 1, DENV - 2, DENV - 3, DENV - 4), which are capable of causing disease and death due to their genetic variety, where the primary infection provides lifelong immunity for the infected serotype and partial - temporary immunity for the remaining serotypes. This exposure becomes in the patient, a risk factor for the development of severe dengue in the event of a new infection [3]. This pathology has been considered a public health problem, classified as a pandemic due to a dispersal of the vector in both tropical and subtropical areas, whose behavior is increasing in the number of cases of both simple dengue, without warning signs and of the type hemorrhagic or severe [4].

The infection can be asymptomatic or express with a wide clinical spectrum that includes severe and non-severe expressions. Severe dengue is life threatening [5]. The distinguishing feature of severe dengue is not the appearance of hemorrhage, but rather the escape of plasma-by-plasma extravasation, which can rapidly lead to dengue shock syndrome (SCD) with hypotension or overt shock [6]. Although dengue shock can be reversed with aggressive fluid administration, the key to therapeutic success lies in its prevention, since after the shock has manifested, the fatality rate can be higher than 10%, even in specialized centers [7].

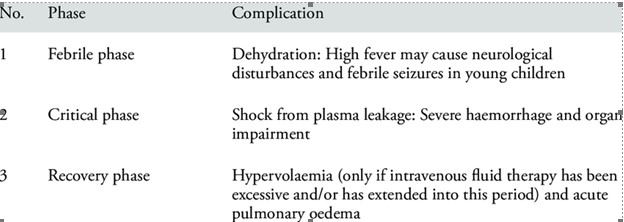

The new classification of the disease issued by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) establishes the criteria for dengue and severe dengue and allows the identification of alarm signs (figure 2) as indicators early shock for the rapid and energetic administration of parenteral fluids [8-9].

Figure 2:

Material & Methods

A detailed bibliographic search of information published since 2015 is carried out, in the databases pubmed, Elsevier, scielo, Update, medline, national and international libraries. We use the following descriptors: Fluid therapy, acute pancreatitis. The data obtained oscillate between 5 and 18 records after the use of the different keywords. The search for articles was carried out in Spanish and English, it was limited by year of publication and studies published since 2015 were used (Table 1).

Table 1: Characteristics of each stage of dengue

Result

The history of severe dengue in Cuba seems to favor this pathogenic interpretation, at least in part. Here the first epidemic of dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock occurred in the Region of the Americas caused by serotype 2 in 1981. During this period, the patients who most frequently presented severe dengue were children under 15 years of age, and of these, the majority were schoolchildren and adolescents (78.1%) who could have previously been infected by the serotype 1 virus that circulated in 1977, while preschool children (18.4%) and infants (3.5%) constituted the minority, whose minor age prevented them from having contact with it [10]. Later, in our country there was no circulation of dengue virus for sixteen years, demonstrated by the epidemiological and serological surveillance of febrile cases and in 1997, during an outbreak located in Santiago de Cuba, only adults, who supposedly maintained antibodies against the virus, aggravated serotype 1 acquired in 1977 [10].

The WHO reports that in recent decades the incidence of dengue in the world has increased enormously, with severe dengue being a life-threatening complication because it involves extravasation of plasma, fluid accumulation, respiratory distress, severe bleeding or organ failure. That is why the importance of investigating and describing the most frequent sonographic findings to detect early the severity and progression of the disease. The number of reported cases rose from 2.2 million in 2010 to 3.2 million in 2015. Europe is faced with the possibility of dengue outbreaks, local transmission was first reported in France and Croatia in 2010, and detected imported cases in three other European countries (WHO, 2017) [12].

In a study conducted in India and published in The British Journal of Radiology, an ultrasound scan was performed on 88 patients between 2 to 9 years of age, 32 between the second or third day of fever, all showing thickening of the gallbladder wall and pericholecystic fluid., 21% had hepatomegaly, 6.25% had splenomegaly and minimal right pleural effusion. Follow-up ultrasound on day 5 to 7 revealed ascites in 53%, left pleural effusion in 22%, and pericardial effusion in 28%. Of 56 patients who underwent fever from the fifth to the seventh day for the first time, all had gallbladder wall thickening, 21% had hepatomegaly, 7% had splenomegaly, 96% had ascites, 87.5% had right pleural effusion, 66% had left pleural effusion and 28 .5% had pericardial fluid. Concluding that the ultrasound findings of thickening of the gallbladder wall with or without polyserositis in a febrile patient should suggest the possibility of dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever (Sai Venkata et al. 2005) [13-14].

In a study developed in Indonesia by H.S. Pramuljo et al. and published in the journal Pediatric Radiology, volume 21. (February 1991), p.100-102, performed abdominal ultrasound in 29 children with dengue hemorrhagic fever and they were correlated with the findings described in the literature, finding that the distribution by age it showed a predominance between 2 and 10 years. Most of the patients were hospitalized on days 3 and 4 of the illness. All cases had pleural effusions, 20 bilateral cases and 9 cases only on the right side, 20 of 29 cases presented ascites, 8 cases had an abnormal wall of the gallbladder and one case, an abnormal liver parenchyma [15].

In the imaging unit of Rawson Hospital. Down Pucará Córdoba, Argentina (2009). Ultrasound examinations were performed on 29 patients with dengue, 18 females and 11 male, with a mean age of 35.6 years. Finding thickening of the gallbladder wall (n = 7) (24%); free abdominal / pelvic fluid (n = 9) (31%); hepatomegaly (n = 5) (17%); splenomegaly (n = 4) (14%); pericholecystic fluid and pleural effusion (n = 2) (7%). Concluding that ultrasound is a useful tool to confirm suspected cases of dengue and to detect early the severity and progression of the disease (Castrillón et al. 2009) [16]. In another prospective, cross-sectional, descriptive study carried out at the Mexican Institute of Social Security in Veracruz, (2006) published in Mediagraphic, where of 132 patients, 21 had classic dengue and 111 with hemorrhagic dengue. Χ² was used for the statistical significance of the sonographic and laboratory findings. Gallbladder wall thickening was observed in 86%, pleural effusion in 66%, ascites in 60%, and acute alithiatic cholecystitis in 36%. Thickening> 3 mm had a sensitivity of 87%, specificity of 48%, concluding that a thickening of the gallbladder wall> 3 mm is a sonographic finding suggestive of dengue hemorrhagic fever (Quiroz et al. 2006) [17]. In 2009, at the Roosevelt Hospital, 97 cases of patients with suspected severe dengue were detected, who underwent abdominal ultrasound, of which 72% were diagnosed with free fluid in the abdominal cavity, pleural effusion in 25% of cases and without findings compatible with dengue hemorrhagic fever in 5%. Given the sensitivity of 87% for gallbladder wall thickening> 3 mm in dengue hemorrhagic fever, this data can be used as a criterion to confirm the disease. A positive predictive value of 90% can serve as indicative criteria for immediate hospitalization and monitoring (Merck, 2016) [18].

Discussion

The clinical picture can range from asymptomatic (inapparent) forms or cause symptoms of varying intensity, including febrile forms with greater or lesser organ involvement, to severe shock and large hemorrhages [19], which in children are expressed according to the different characteristics of pediatric age, since the anatomical and functional properties of the infantile organism are different from those of the adult [20]. Severe forms are characterized by signs of circulatory failure and hemorrhagic manifestations. These usually occur at the time of the disappearance of the fever, it coincides with the critical period of the disease and the pathophysiological substrate is capillary leakage. On occasion, the dengue virus mainly affects internal organs and causes encephalitis, myocarditis or hepatitis, which can have a fatal course [21].

Abdominal pain or abdominal tenderness is the most frequent alarm sign in patients with dengue (62.4%). The second most frequently observed alarm sign was the concomitant increase in hematocrit with the rapid decrease in platelets, which was found in 43.2% of patients with dengue. The next most frequent sign was the clinical accumulation of fluids, which was found in almost a third (34.5%) of the patients studied. The presence of hepatomegaly greater than 2 centimeters was the next most frequent sign, observed in 20.9% of the patients, followed by the presence of mucosal bleeding (14.9%). Both the presence of persistent vomiting (5.9%), as well as lethargy or irritability (3.9%), were the least frequent warning signs in the dengue patients studied. Dengue shock occurred in 27% (221 cases) of the patients studied [22].

Abdominal pain or abdominal tenderness is the most frequent alarm sign in patients with dengue (62.4%). The second most frequently observed alarm sign was the concomitant increase in hematocrit with the rapid decrease in platelets, which was found in 43.2% of patients with dengue. The next most frequent sign was the clinical accumulation of fluids, which has been found in almost a third (34.5%) of the patients studied. The presence of hepatomegaly greater than 2 centimeters would be the next most frequent sign, observed in 20.9% of patients, followed by the presence of mucosal bleeding (14.9%). Both the presence of persistent vomiting (5.9%), as well as lethargy or irritability (3.9%), have been the least frequent warning signs. Dengue shock occurs in 27% of patients [23].

When analyzing the presence of alarm signs at any time during the course of the disease, it is found that except for the presence of frequent vomiting, the remaining six warning signs of dengue (abdominal pain, clinical fluid accumulation, mucosal bleeding, lethargy / irritability and increased hematocrit concomitant with decreased platelets) are more frequent (p <0.05) in those cases of dengue with shock compared to cases that never developed shock. The warning signs will be less frequent in those cases of shock, but only the clinical accumulation of fluids and the concomitant increase in hematocrit are significant (p <0.05) [24].

The increase in hematocrit concomitant with the rapid decrease in platelets is the second most frequent sign, the present study coincides with a similar result found by Thein et al in 2013, who reported this sign as the second in frequency during the entire evolution of the disease. that occurs during dengue [25].

The third most frequent alarm sign was the clinical accumulation of fluids. The frequency of this sign is explained by the main pathophysiological event of dengue: plasma leakage [12]. The presence of ascites in dengue patients was reflected in 91.6% of the cases, it was a rare sign (1%) [26]. Detection of clinical fluid accumulation in dengue patients varies according to the means used (x-ray, ultrasound, physical examination). Until now, the best method registered for the detection of these fluid accumulations is ultrasound on at least 3 different occasions regardless of the clinical status of the patient in order to find these types of findings (ascites, gallbladder wall thickening, pleural effusion, perirenal collections or pararenal) [27].

The moment of identification or detection of the warning signs plays a fundamental role in interpreting their usefulness in preventing complications in dengue. In patients who develop dengue shock compared to patients who never experienced shock, this finding could lead to the warning signs playing a risk role. However, when the temporality is controlled and only the warning signs are studied before the onset of shock, two things are observed: a decrease in the frequency of the warning signs and that there is no longer individual significant difference (for each sign of alarm) when compared with the group of patients who did not develop shock [28].

CONCLUSION

Because dengue is an infection that constitutes a very frequent public health problem in general emergency services and is one of the most consulted pediatric emergencies, care protocols and prevention programs for this disease should be frequently reviewed. Thus, guaranteeing a reduction in the rates of infection-morbidity and mortality in adults and children and avoiding the evolution of classic dengue pictures to clinical pictures of dengue shock. The surveillance of alarm signs such as early detection of these fluid collections in perirenal and pararenal areas is indicated in all available protocols and guides, a situation that guides us to changes in hematocrit concentration and warns of the development of involvement multiorgan and subsequent establishment of a dengue shock state. So far, and taking into account the articles reviewed, it can only be stated that dengue shock with fluid collections in these areas (perirenal and pararenal) is one of the strongest stages of dengue infection and that if not treated correctly, it can mark significant sequelae in the patient and even death.

Reference

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Dengue y dengue grave. 2017.

- Juan Lage R, Herrera Graña T, Simpson Johnson B, Zulueta Torres Z. Aspectos actualizados sobre dengue. Rev Inf Cient, 2015; 90(2): 374-390.

- Malavige GN, Ogg GS. Pathogenesis of vascular leak in dengue virus infection. Immunology, 2017; 151(3): 261-269.

- Instituto Nacional de Salud. Boletín epidemiológico semanal 01 de 2019. Boletín epidemiológico seminal, 2018: 1-23.

- Trugilho MRDO, Hottz ED, Brunoro GVF, Teixeira Ferreira A, Carvalho PC, et al. Platelet proteome reveals novel pathways of platelet activation and platelet-mediated immunoregulation in dengue. Kuhn RJ. PLOS Pathogens, 2017; 13(5): e1006385.

- Álvarez A, Guerrero M, Gutiérrez I. Investigación dirigida: Criterios de gravedad con respecto a dengue grave [Tesis de Licenciatura]. San José: Universidad de Iberoamérica; 2017.

- Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. 2013: 504-507.

- World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue. 2015.

- MINSAP. Guías para la asistencia integral a pacientes con dengue [Internet] 2011: 1-41.

- Dotres Martínez C, Machado Fallat G, Torres Martínez E, Sabatela Carpio R, Hernández Rojo E, et al. Algunos aspectos clínicos durante la epidemia de Dengue hemorrágico en Cuba. Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 1987; 3(2): 148-157.

- Valdés L, Guzmán MG, Kourí Delgado J, Carbonell I, et al. La epidemiología del dengue y del dengue hemorrágico en Santiago de Cuba, 1997. Rev Panam Salud Pública, 1999; 16-25.

- OMS (Organización mundial de la salud). 2018. Dengue y dengue grave. Ginebra, suiza. Disponible en http://www.who.int/media entre/factsheets/fs117/es.

- Venkataasí, De B Krishnnan R, 2005. Role of ultrasonido un dengue deber. The British Journal of Radiology 78: 416-418.

- Kalayanarooj S. Dengue classification: current WHO vs. the newly suggested classification for better clinical application? J of the Medical Association of Thailand, 2011; 3: S74-84.

- WHO. Dengue haemorrhagic fever: Diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and control. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1997.

- Hang VT, N Minh N, Trung DT, Tricou V, Yoksan S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of NS1 ELISA and lateral flow rapid tests for dengue sensitivity, specificity and relationship to viraemia and antibody responses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2009; 3(1): 360.

- Feigin RD, Cherry JD. Dengue y fiebre hemorrágica del Dengue. Tratado de Infecciones en Pediatría. Vol 2. Segunda ed: Interamericana Mc Graw-Hill, 1992: 1410-1420.

- Halstead SB. Dengue/fiebre hemorrágica dengue. In: Interamericana M-H, editor. Tratado de Pediatría de Nelson I, 2001; p. 1102-1105.

- De Madrid AT, Porterfield JS. The Flaviviruses (group B arboviruses): A cross neutralization study. Gen Virol, 1974(23): 91-96.

- Halstead SB, Nimmannitya S, Yamarat C, Russell PK. Hemorrhagic fever in Thailand; recent knowledge regarding etiology. Jpn J Med Sci Biol, 1967: 96-103.

- Martinez E. Dengue. Rio de Janeiro: Editorial Fio Cruz; 2005.

- Setiawan MW, Samsi TK, Wulur H, Sugianto D, Pool TN, et al. Dengue haemorrhagic fever: ultrasound as an aid to predict the severity of the disease. Pediatric Radiology, 1998; 28(1): 1-4.

- Premaratna R, Bailey MS, Ratnasena BG, de Silva HJ. Dengue fever mimicking acute appendicitis. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2007; 101(7): 683-685.

- Binh PT, Matheus S, Huong VT, Deparis X, Marechal V, et al. Early clinical and biological features of severe clinical manifestations of dengue in Vietnamese adults. J Clin Virol, 2009; 45(4): 276-280.

- Chongsrisawat V, Hutagalung Y, Poovorawan Y. Liver function test results and outcomes in children with acute liver failure due to dengue infection. The Southeast Asian Journal of tropical medicine and public health, 2009; 40(1): 47-53.

- Souza LJ, Alves JG, Nogueira RM, Gicovate Neto C, Bastos DA, et al. Aminotransferase changes and acute hepatitis in patients with dengue fever: analysis of 1,585 cases. The Brazilian J of infectious diseases, 2004; 8(2): 156-163.

- Salgado DM, Eltit JM, Mansfield K, Panqueba C, Castro D, et al. Heart and skeletal muscle are targets of dengue virus infection. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 2010; 29(3): 238-242.

- Kularatne SA, Pathirage MM, Gunasena S. A case series of dengue fever with altered consciousness and electroencephalogram changes in Sri Lanka. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2008; 102(10): 1053-1054.

Recent Comments